This piece was first published in The Freethinker.

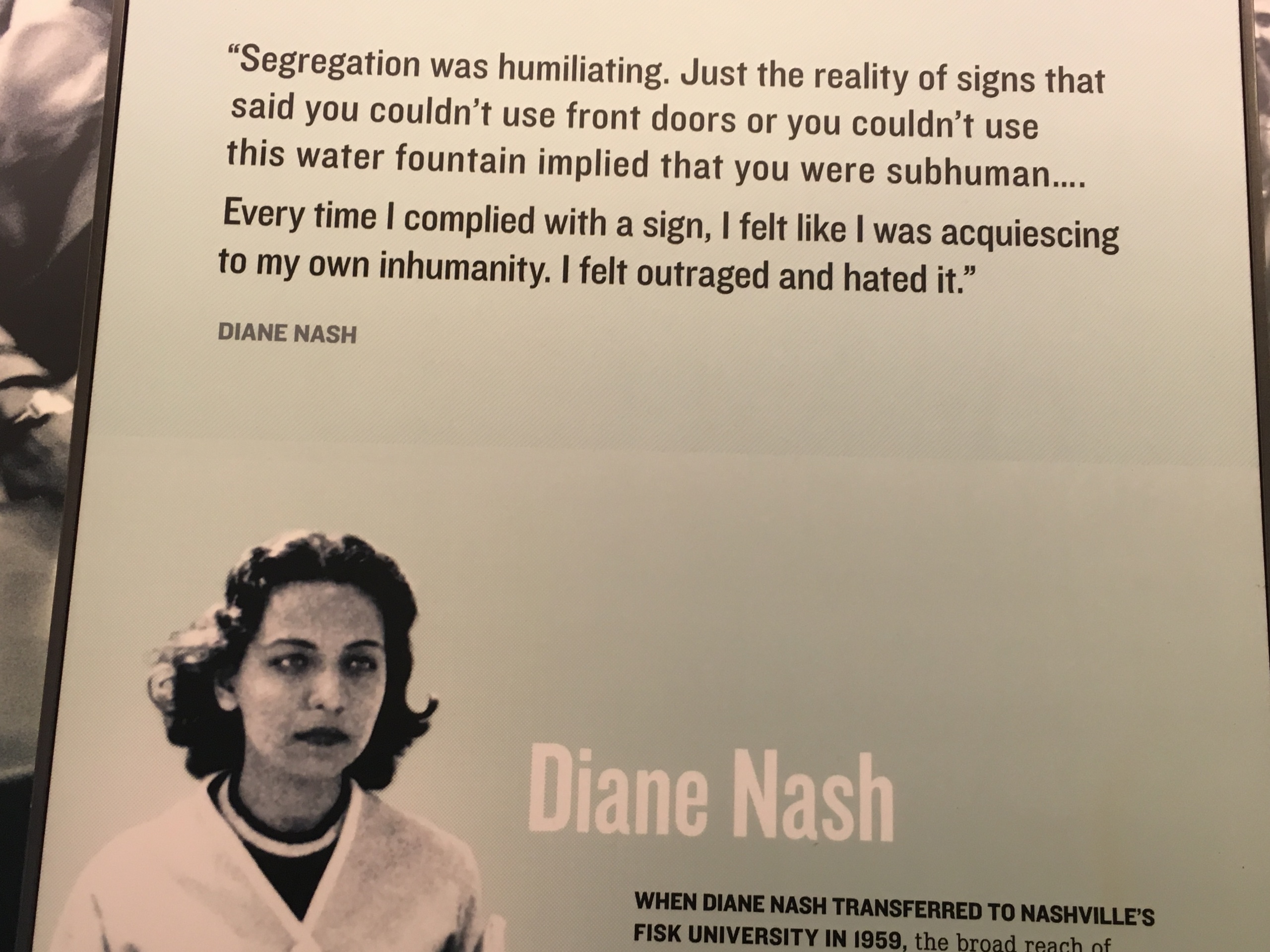

Segregation was humiliating. Just the reality of signs that said you couldn’t use front doors or you couldn’t use this water fountain implied that you were subhuman … Every time I complied with a sign, I felt like I was acquiescing to my own inhumanity. I felt outraged and hated it.

– Diane Nash, a leader of the 1960s US Civil Rights Movement

When the Hezbollah came to segregate the girls from the boys at my school in Iran in 1980 after an Islamic regime took power, I remember wondering what was so wrong with me that I had to be separated from my male friends.

I was only 12 at the time.

I soon learnt that segregation was a “necessity” because girls over the age of nine (considered the age of maturity) are “sources of fitnah“, “temptations that incite men’s lust” eventually leading to adultery (Zina). And that gender segregation “protects” society from “moral decay” and “sex anarchy”.

Better to be segregated, I was told, than to have to be stoned to death for adultery.

I was elated, therefore, when a Court of Appeal found that gender segregation – including in the classroom, corridors, school clubs, play areas and school trips – at Al-Hijrah school in Birmingham was discriminatory.

Given the rise of gender segregation at schools and universities in this country (including at the Rabia School in Luton, Madani school in Leicester, the LSE, Queen Mary University of London as well as Orthodox Jewish schools), the land-mark decision should have far-reaching effects in favour of the rights of minority women and girls in particular. The decision is also a victory against the religious-Right which uses religion in the educational system to police and control women and girls.

The basis for gender segregation (as well as veiling, banning women’s singing, prohibiting hand-shaking with women, male guardianship and so on) is that a woman’s and girl’s place is in the home, that she is lesser than a man or boy and that mixing with her will lead to “corruption”.

In Bas les Voiles, Chahdortt Djavan argues that the psychological damage done to girls from a very young age by making them responsible for men’s arousal is immense and builds fear and feelings of disgust at the female body.

Sayyid Maududi, the founder of Jama’at-i Islami (the Salafis of South Asia that are running some of the mosques, schools and Sharia courts here in Britain) explains why segregation is important in his book Purdah and the Status of Women in Islam:

In the eyes of law, adultery implies physical union only, but from the moral point of view every evil inclination towards a member of the Opposite sex outside marriage amounts to adultery. Thus, enjoying the beauty of the other woman with the eyes, relishing the sweetness of her voice with the ears, drawing pleasure of the tongue by conversing with her, and turning of the feet over and over again to visit her street, all are the preliminaries of adultery, nay, adultery itself.

Sharia courts here in Britain reinforce this point of view. For example Haitham al-Haddad, who was until recently a Sharia judge at the Leyton Sharia council and who testified at the Home Affairs Committee Sharia Councils inquiry (which was by the way quietly closed without any resolution), says on gender segregation:

What really amazes me, however, is the denial many people suffer when it comes to gender interactions in the 21st century. Even more astonishing is the blind eye that countless Muslims turn towards the masses of cases in Islamic law and jurisprudence in regulating the relationship between men and women, in particular minimising ikhtil?t (intermingling) between sexes. The Prophet (sallAll?hu ‘alayhi wasallam) said, ‘I am not leaving behind a more harmful trial for men than women’.

Those who defend gender segregation as being “separate but equal” ignore the reality that women and men are not equal in any sense of the word. In fact, “one is confined while the other is at large.”

Cultural relativists who would never defend inequality between non-minority women and men or segregation based on race excuse gender segregation because they say it is “voluntary” and a “choice”. Aside from the fact that Islamists use rights language to curtail rights, of course women and girls can sit where they choose. “What is discriminatory”, however, says Algerian sociologist Marieme Helie Lucas “is to assign a place to somebody, whatever that place may be. It says: keep to your place; to women’s place!”

In her witness statement to the Court of Appeal, Pragna Patel, Director of Southall Black Sisters stated:

The impact of segregation is detrimental to girls since its aim of gender segregation is not to promote gender equity but to reinforce the different spaces – private and public – that men and women must occupy, and their respective stereotyped roles which accord them differential and unequal status.

In a piece entitled “Education and the Muslim Girl”, Saeeda Khanum quotes an interview with Liaqat Hussein from the Council for Mosques, which shows the real aims of gender segregation:

The struggle, he said, is between Islam and godlessness, which in the schools takes the form of coeducation, Darwinian theory, female emancipation and Muslim girls running away with non-Muslim boys. There’s no such thing as freedom in religion. You have to tame yourself to a discipline. We want our children to be good Muslims, whereas this society wants children to be independent in their thinking.

For now though, we should celebrate this important decision. As Pragna Patel of Southall Black Sisters stated:

We very much welcome the judgment and its recognition that gender segregation can be unlawful and discriminatory, especially in contexts where the practice is tied to the rise of religious fundamentalist and conservative norms. For over three decades, we have seen how regressive religious forces have targeted schools and universities as a means by which to control and police female sexuality in minority communities.

The imposition of gender segregation, dress codes and sharia laws are just some means by which gender inequality is legitimised and promoted despite the serious and harmful consequences. This judgment is a vital step forward in our effort to persuade the courts and state bodies to take account of the reality of the misogyny and gender stereotyping that is promoted in our schools and universities in the name of religious and cultural freedom. We are delighted that the court has seen through this and upheld the equality principle.