Young Muslim woman raped and her children kidnapped by violent husband after trying to obtain divorce through ‘sharia courts’, Carmon Report, 30 January 2022

A YOUNG British-Pakistani woman was raped by her husband and left fearing for her and her children’s lives after a sharia court forced to her reveal her address and to try and get back with him.

Lubna, which is not her real name, had already obtained a legal divorce through the British courts from her violent husband, but after her mother was pressured by the Muslim career in which they lived in London, she was forced to seek a sharia divorce as well.

First the clerics tried to persuade her to attempt a reconciliation with her abusive husband. Then, after they disclosed her address, he threatened to kill her, kidnapped her children, and subjected her to an horrific rape that left her needing an abortion, reports MailOnline.

Lubna, who was brought up in the north of England in a middle-class family, was sexually and physically abused by her husband – who she joined with under an arranged marriage.

But after he left her to pursue a new life in America with a new woman, Lubna decided she would file for divorce through the British legal system.

She was given a restraining order to protect her from her furious husband – who had returned to the UK to fight the split – and was granted custody of their children.

Her nightmare began however when her estranged husband told a prayer meeting at her local east London mosque that she was a “loose women being pimped out by her widowed mother”.

Although at least one imam knew the horrific background to her marriage, a group from the mosque visited her family to persuade her to return. When that failed, the imam, an old family friend, put more pressure on Lubna to go to the sharia court near London’s Regent’s Park.

To avoid shaming her devout Muslim mother Lubna agreed but the “judges” didn’t care about the plight she’d suffered at her violent ex’s hands and repeatedly told the young woman and her mother to be “silent”.

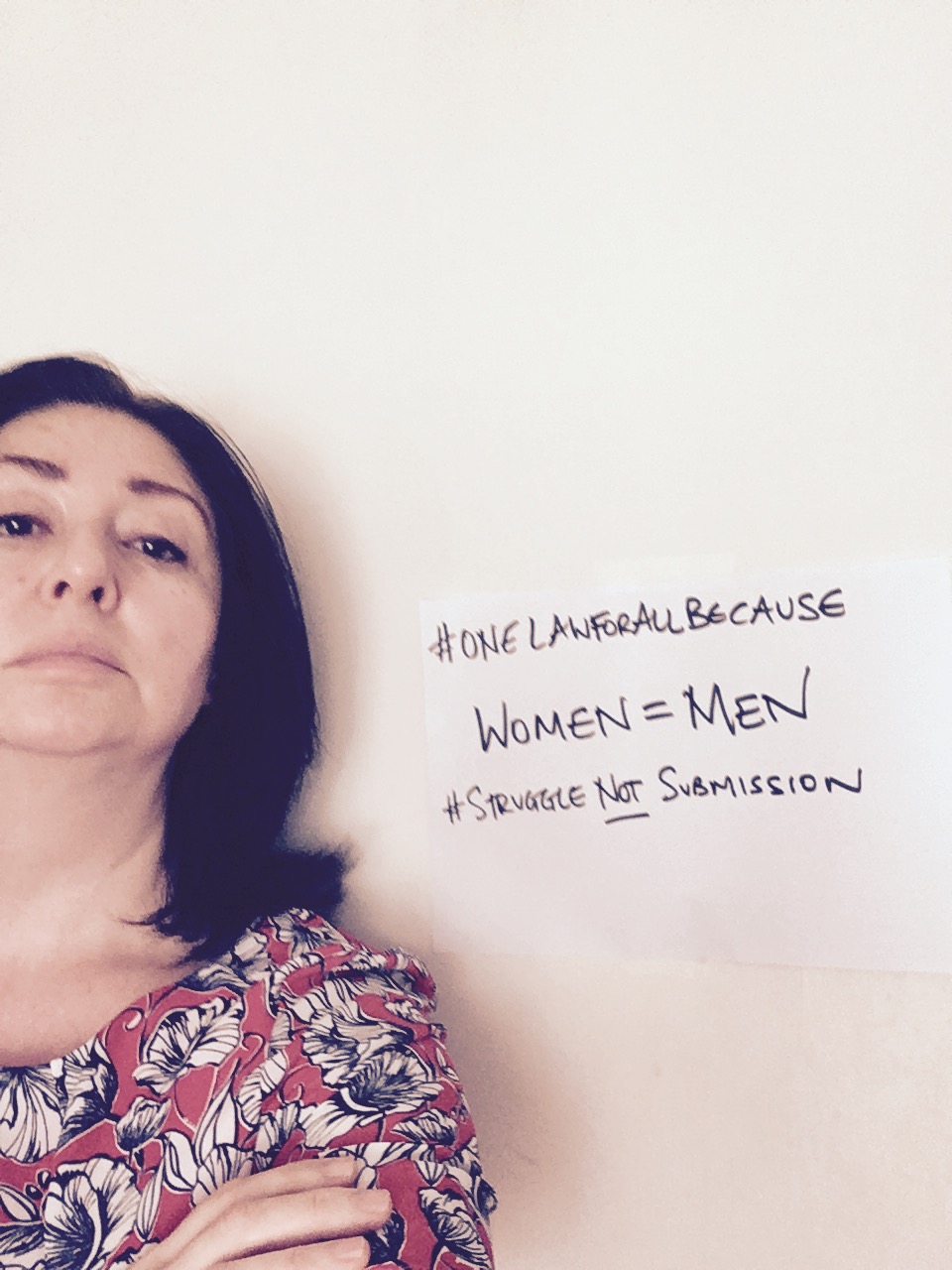

Speaking to the One Law for All campaign which is working to ban sharia courts to improve Muslim women’s rights, Lubna said: “The court was incredibly difficult. My mother and I were repeatedly told to be silent. None of the information from the civil proceedings, including non-molestation orders, was admissible in the sharia court.

“When my ex-husband said he wanted a reconciliation, the judges said I should comply.

“I tried to tell them about the violence and abuse I had suffered throughout the marriage, but was advised to be quiet. My mother was also silenced.”

She faced intrusive questioning about the last time she had sex with her husband – crucial, the judges told her, to determine exactly when their relationship had ended. She was also forced to disclose her address.

Astonishingly however when Lubna’s mum sought advice from Islamic scholars in Pakistan and India – they told her a civil divorce was sufficient to end the marriage.

As a result they never finished the sharia divorce and the young Muslim went on to try and rebuild her life.

For more than 30 years sharia courts enforcing Islamic law have been operating quietly across Britain. But two official inquiries have put them in the spotlight amid accusations that they discriminate against women.

Very little is known about them, even their number. One study by the University of Reading puts it at 30, while the British think tank Civitas estimates there could be as many as 85.

Sharia courts or councils, as they prefer to be called, mainly pronounce on Islamic divorces, which today make up 90 per cent of the cases they handle.

They range from groups of Muslim scholars attached to a mosque, to informal organisations or even a single imam.

But while they are aimed at helping resolve family and sometimes commercial conflicts within the Muslim community, some stand accused of undermining women’s rights.

Campaigners cite instances where courts have refused to grant religious divorces to women who are victims of domestic abuse, and accuse them of legitimising violence, including marital rape, as was the case with Lubna.

The government and MPs on parliament’s home affairs committee both opened inquiries this year into whether the councils are actually compatible with British law.

They are looking into the function and possible discriminatory practices of the courts.

The first sharia court appeared in London in 1982 under the government of Margaret Thatcher, who rolled back state intervention in many areas, including mediation in family conflicts, which was delegated to faith groups.

The decisions of sharia courts are not legally binding, but they represent a strong moral and social constraint for those who use them.

For Shaista Gohir, the chairwoman of Muslim Women’s Network UK who gave evidence to the parliamentary inquiry, sharia councils are useful for Muslims but should be framed by a “strong code of conduct”.

She also urged the government to make civil marriage obligatory for couples marrying under Islamic law, to ensure women are legally protected, saying that 40 percent of women who contact her organisation only had religious marriages.

But for other Muslim feminists, the courts constitute a “parallel legal system” and should be banned altogether.

An open letter calling for them to be outlawed was signed by more than 200 national and international women’s organisations, while legislation which would limit the scope of sharia councils has been put forward by a member of the House of Lords.

“They are discriminatory, they are abusive, they endorse and legitimise violence,” in particular marital rape, Maryam Namazie, spokeswoman for the One Law for All campaign, told AFP.

She added: “These courts are linked to the rise of the Islamist movement. They are now saying that to be a good Muslim you have to go to these courts to get a divorce. It’s not the case.”

Swiss political commentator Elham Manea, the author of “Women and Sharia Law” who has studied the phenomenon for four years, said the first councils were set up by Islamist groups.

“They have been working with a kind of a tacit approval of British establishment,” she said.

“There is a certain kind of hesitancy from British institutions to interfere in what they consider is internal affair to the Muslim community.”

What is sharia law?

Sharia is the Islamic law that codifies the individual and collective rights and responsibilities of Muslims.

Stemming from the Koran and the Sunnah – teachings attributed to the prophet Mohammed – it is a collection of rules, restrictions and sanctions covering personal and family status, criminal and public law.

It is imposed with varying degrees of strictness in certain Muslim countries and is subject to interpretation.

Among the punishments, it calls for the death penalty for murder, 100 lashes for adultery – whether by a man or woman – and the amputation of the right hand for theft.

Adultery is punishable by death by stoning in Muslim countries where sharia has the force of the law.

Marriages can be ended in three ways – an annulment pronounced by a qadi, or judge; divorce by mutual consent, or unilateral repudiation (talaq), usually by the man.

A divorce demanded by the woman (khula) generally requires giving up financial assistance, including any return of the dowry.

Under sharia, the right to divorce rests with the man. A civil divorce is therefore not automatically valid under Islamic law – only if the man agrees.

In Britain, sharia councils or courts mainly handle Islamic divorces. Their decisions are not legally binding but have weight in the Muslim community.